John Newton: From Disgrace to Amazing Grace

by Jonathan Aitken, 2007, Crossway Books, ISBN 978-1-58134-848-4

Follow link for an Introduction to the Cloud of Witnesses series

Follow link for an Introduction to the Cloud of Witnesses series

In his biography of John Newton, Jonathan Aitken colors a canvas with broad strokes of a physical life and spiritual influence enabled and preserved by the grace of God. Drawn from an apparent deep study of both long-available and recently accessible origin archives of Newton’s life, Aitken explores the sea captain turned preacher’s troughs and peaks while leaving the reader wanting more but appreciating the concise and enriching overview.

|

| Source: http://www.christianitytoday.com/images/67452.jpg?w=700 |

That saved a wretch like me.

I once was lost but now I'm found,

Was blind, but now I see.

Untiringly rebellious from his youth, Newton brought grief to his parents and employers alike. Born July 24, 1725, to Captain John and Elizabeth Newton of London, young John lost his mother and spiritual mentor when he was not quite seven years old. She taught him to read the Bible by the age of four when, Newton said later in life, “I could read as well as I can now” (p. 27). John, Jr. brought much grief to his father who repeatedly used his respected position to bail his son out of difficulties born of his own impetuous decisions. As a ship’s hand, he was AWOL, severely punished and finally traded away by his military overseers, only to find himself in worse hands as a slave in Africa. Rescued from slavery, Newton became an ungrateful deckhand on the Greyhound headed west across the Atlantic Ocean to the American colonies.

'twas Grace that taught,

my heart to fear.

And grace, my fears relieved.

How precious did that grace appear,

the hour I first believed.

my heart to fear.

And grace, my fears relieved.

How precious did that grace appear,

the hour I first believed.

Yet shunned by the troublemaking, blaspheming Newton, God snatched him from a Christ-less eternity. Aitken reports that on the return trip to England a mighty storm arose on March 10, 1748. The Greyhound was suddenly in peril of sinking with Newton surrounded by water in the hold of the ship . Newton “rushed to the ladder and climbed toward the deck [when] the captain ordered him to go back down and fetch a knife. As Newton obeyed the order, another man climbed the ladder in his place, reached the deck, and was immediately swept overboard.” Newton later wrote: “We had no leisure to lament him nor did we expect to survive him long” (p. 75).

In the days of running pumps until the point of exhaustion and suffering dehydration and hunger as the ship slowly limped East, Newton remembered his spiritual upbringing and found one of the few items to survive the storm—a Bible. He had no trouble being motivated to read it. Aitken rehearses three Scriptures that weighed heavy on Newton’s mind:

Luke 11.13 – If ye then, being evil, know how to give good gifts unto your children: how much more shall your heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to them that ask him?

John 7.17 – If any man will do his will, he shall know of the doctrine, whether it be of God, or whether I speak of myself.

Luke 15.11-32 – the parable of the prodigal son (p. 83)

On April 8, 1748, John Newton and the survivors stepped on the soil of Ireland—John a baby Christian: “About this time I began to know that there is a God who hears and answers prayers” (p. 84).

Through many dangers, toils and snares,

I have already come.

'tis grace that brought me safe thus far,

and grace will lead us home.

I have already come.

'tis grace that brought me safe thus far,

and grace will lead us home.

Over the next seven chapters of his book, Aitken takes his readers on a journey with Newton as God is preparing him to become a minister of the Gospel. Aitken explains what seems impossibly contradictory for a Christian today—Newton became a captain of a slave ship. Aitken:

In mitigation of Newton’s position, it may be argued that not one single Christian leader in mid-eighteenth-century England had realized, let alone complained, that slave trading was a spiritual and humanitarian abomination. This, however, is an explanation for Newton’s blindness, not an excuse for it (p. 112).

Newton became a minister only after considerable deliberation and difficulty. He needed much training and encouragement by others—they, too, trophies of God’s grace. Alexander Clunie, a Dissenter, “taught Newton how to pray aloud in company, how to engage in dialogue with fellow believers, how to study the Bible, and how to give witness or personal testimony explaining that the gift of God’s grace had changed his life” (p. 124). On February 11, 1750, John Newton married Mary (Polly) Catlett beginning a shared life of ministry until her death in 1790, seventeen years before he would join her in Glory.

The Lord has promised good to me,

His word my hope secures.

He will my shield and portion be,

as long as life endures.

His word my hope secures.

He will my shield and portion be,

as long as life endures.

An exceptional and innovative pastor and preacher, Newton devoted the rest of his life to know and communicate God’s word. He started with his autobiography, An Authentic Narrative. It told the story of what Aiken has claimed as his subtitle—From Disgrace to Amazing Grace.

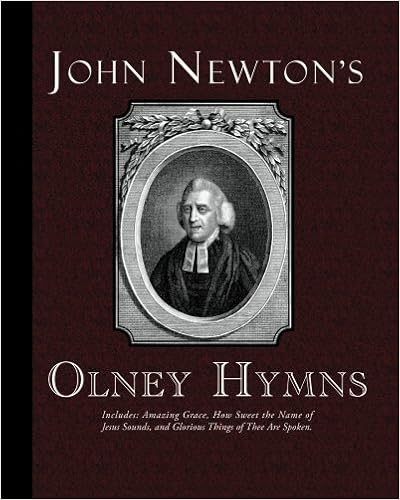

His first pastorate was as the preacher in the Church of England parish at Olney where he endeavored “to preach what I ought and to be what I preach” (p. 179). But he was an independent a clergyman as the Church of England would suffer—frequently giving and receiving encouragement from nonconformist Baptist, Methodist and Dissenting ministers. His innovations included children’s, youth and prayer ministries (p. 188).

He never ceased to recognize the grace of God in his life—a rebel, a blasphemer, a slave ship captain, a poor clergyman, a humble statesman. Newton sought to mimic the humility of the Apostle Paul, arguing (according to Aiken) “that a proud Christian is as much an oxymoron as a sober drunkard or a generous miser” (p. 203).

Newton coauthored the Olney Hymns with renowned English poet, William Cowper. This collection of poems was sung at Olney and, later, innumerable churches both in England and America “partly because hymn singing was an experimental form of worship that the parishioners seemed to enjoy, and partly because hymns could be good expository material for spiritual teaching” (p. 215).

|

| Source: https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51QV73RSbbL._SX398_BO1,204,203,200_.jpg |

When we've been there ten thousand years,

bright shining as the sun.

We've no less days to sing God's praise,

than when we first begun.

bright shining as the sun.

We've no less days to sing God's praise,

than when we first begun.

Ironically, the well-known tune for Amazing Grace and the above, typically final verse were not Newton’s, but rather the creation of the descendants of the very slaves that he helped to ship to the Southern states of America. For, “Newton wrote Amazing Grace as he wrote all his hymns, with no tune in mind” (p. 233).

The final one third of Aiken’s book tells the story of Newton’s call to London in 1779 at the age of 54 where he pastored St. Mary Woolnoth and lived until his death in 1807. Excerpts of these days follow.

Newton said, “I have seldom one hour free from interruption… [N]ight comes before I am ready for noon and the week closes when according to the state of my business it should not be more than Tuesday” (p. 241).

When his wife Polly protested his busyness, he responded, “I am sufficiently indulgent to Mr. Self. Do not fear my overworking him. I need a spur more than a bridle” (p. 260).

Aiken notes from a careful reading of Newton’s extensive personal diaries, “At all levels his ministry was a powerful one, sustained by his private prayers. Newton’s secret was prayer. His humble, grateful, confessional, and intercessory prayer life kept him in a close relationship with his Lord and drover every aspect of his private thoughts and public ministry” (p. 269).

From his first sermon at St. Mary Woolnoth: “The Bible is the grand repository of the truths that it will be the business and the pleasure of my life to set before you. Every attempt to disguise or soften any branch of this truth in order to accommodate it to the prevailing taste around us either to avoid the displeasure or court the favor of our fellow mortals must be affront to the majesty of God and an act of treachery to men” (p. 272).

Hyper Calvinism encroached upon Christian churches in Newton’s days. He was an anomaly in the Church of England—an “enthusiast”, an evangelist. A critic confronted him: “’[S]ometimes when I read you and sometimes when I hear you I think you are a Calvinists; and then again I think you are not.’ But Newton responded, ‘I am more of a Calvinist than anything else, but I use my Calvinism in my writings and my preaching as I use this sugar [in my tea.]’ Newton then picked up a lump of sugar, dropped it in his cup, stirred it, and concluded, ‘I do not give it alone and whole but mixed and diluted’” (p. 286).

Newton was a friend and mentor of William Wilberforce, viewed by many as the single loudest voice in the storm to overturn and British slave trade. Aikten quotes a telling phrase from Newton’s Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade, “I hope it will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders” (p. 319).

As he entered his 76th year on the day of his birth, August 4, 1800, his diary to the Lord included a reflective entry on the theme of God’s lifelong grace in Newton’s journey: “What a striking proof is my history of the deceitfulness and desperate wickedness of the heart, and of Thy wonderful long-suffering patience and mercy” (p. 341).

In the waning days of his death on December 21, 1807, Newton conveyed to a friend, “My memory is nearly gone, but I remember two things: That I am a great sinner and that Christ is a great Savior” (p. 347).

Aitken leaves his reader with practical “take home” truths to challenge the mind and spirit of those seeking to emulate Newton’s life and ministry:

“The first lesson that any new believer can learn from Newton is that a sinner is not transformed into a Christ-centered soul by a single conversion experience but by the long, unremitting, and courageous effort that conversion begins. It was only after he had surrendered his will to a completely new set of godly rules, disciplines, and teachings that his journey of change began to make real progress.

“Second … It is difficult is come to faith on one’s own without good teachers. Until Newton met Captain Alexander Clunie, his first spiritual mentor, he was like a seed springing up too fast in stony ground.

“Third … Newton made evangelistic innovations and embarked on an ambitious program of pastoring visiting that could make a good blueprint of lessons for any modern minister arriving to take charge of a new church. He won the confidence of his congregation by sound biblical preaching. He reached out to the wider community by diligent pastoral work.

“[Finally] … The secret of Newton’s relationship with God was his prayer life. Because he kept such meticulous diary records it is possible to study in detail how often Newton prayed (at least five hours a day), who he prayed for (a vast list), and what his prayer priorities were (gratitude to the Lord and humility)” (pp. 352-354).

Comments

Post a Comment