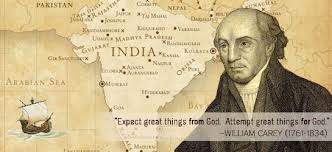

William Carey: The Father of Modern Missions

by S. Pearce Carey, 1923, The Wakeman Trust, London, ISBN 978-1-870855-61-7

S. Pearce Carey, William Carey’s great grandson, offers a family perspective on the brilliant mind and consecrated life of one who first left England to reach to the regions beyond with the Gospel of Jesus Christ. From the historical setting of his birth on August 17, 1761, to the legacy he left in the land of India and upon the world following his death on June 9, 1834, Carey’s life story leaves its reader with a sense of enablement to attempt great things for God. For William Carey once said,

Expect great things from God. Attempt great things for God.

| Source: https://edhird.files.wordpress.com/2013/05/william-careymap.jpg |

It was 32 years before Carey left England never to return. He was motivated by the lives and stories of such men as Captain John Cook, explorer of the islands of the South Pacific and mapper of New Zealand and present day Australia; slave trader turned abolitionist and “enthusiast” Anglican preacher John Newton; Methodist Nonconformist John Wesley; novelist Daniel Defoe whose Robinson Crusoe was so realistic that readers refused to believe it was fiction; bold David Brainerd, evangelist to hostile American Indians; and, not to be outdone, an adventuresome uncle from 18th Century Canada.

As a boy, Carey loved the fields and gardens, but his father insisted he pursue shoemaking. Tainted by the wickedness of his companions, his youth was characterized by hypocrisy until “when seventeen and a half he exchanged the Pharisee’s righteousness for the publican’s meekness, and flung his helpless, sin-stained soul upon the mercy and kindness of Christ” (p. 26). Carey became a committed, evangelistic Baptist at a time when its “pulpit doctrine … was often extravagantly hyper-Calvinistic” (p. 8). He eschewed the “liberal line on baptism … not requiring submission to the ordinance for membership,” having “reinvestigated the New Testament, and was led to the conviction that the ordinance of baptism was appointed for those of conscious faith and consecration” (S. Pearce Carey’s emphasis) (p. 34).

William Carey married Dorothy Plackett on June 10, 1781, as he continued his bi-vocational career as cobbler and preacher—a controversial one at that. Admitted in the ministers’ fraternal of Northampton Associates as a late-20 something, he pressed the others to consider (as S. Pearce Carey quotes him) “whether the command given to the apostles to teach all nations was not binding on all succeeding ministers to the end of the world, seeing that the accompanying promise was of equal extent” (p. 47). Of course, here William was referring to Matthew 28.19-20, “Go ye therefore and teach all nations … and, lo, I am with you alway, even unto the end of the world.” This met with swift and vociferous hyper-Calvinist objection: “Young man, sit down, sit down! You’re an enthusiast. When God pleases to convert the heathen, He’ll do it without consulting you and me” (p. 47).

Meanwhile, William and Dorothy continued for the first decade of their lives together developing missionary zeal by first accepting a call to an anemic church at Harvey Lane and simultaneous becoming tireless church planters of five additional churches (p. 59). But Carey cast his eyes beyond the shores of England. He embarked on a study of the regions beyond carefully cataloguing and mapping the “religious complexion” and populations are far-away places (p. 67). No doubt prompted by his curiosity with the explorations of Captain John Cook, “as far as his map was concerned, even pin-point dottings on the oceans were precious in his sight. His interest in islands is most marked,” says S. Pearce Carey (p. 68).

Carey began to develop a strategy for world-wide missions: “If lay workers are also sent with ordained missionaries, whose knowledge of farming, fishing, and fowling shall supply the mission’s creaturely necessities, the initial outlay will often be the only and the whole expense” (p. 69). But his strategizing was subservient to prayer:

Choose ‘men of piety, prudence, courage, and forbearance’; men of sound knowledge of the Word and the Gospel; men prepared to forgo comforts and endure hardships. Let them above all be instant in prayer, and they will not fail, especially if they be quick to discern and develop the faculties of their converts, who, with their inborn understanding of the people, must always be a county’s chief evangelists” (p. 69-70).

We must pray, for without the Spirit all is vain. Prayer … is the beginning of all blessing and victory, the first link to the divine chain, the key to Heaven’s treasury” (p. 70).

Prayer is basic for the spread of the Gospel. All, even the poor and illiterate, can swell its force. However, we must plan and plod as well as pray, or else the children of this generation will again shame the children of light. Then we must pay as well as pray and plan (p. 70).

All of William Carey’s burden seemed to come to a head on May 31, 1792, at a meeting of the Northampton Association of Particular Baptist churches when he voiced the most memorable words of his message to the ministers and messengers assembled:

Expect great things from God. Attempt great things for God.

And so was formed the Particular Baptist Society for the Propagation of the Gospel amongst the Heathen (the “Society”). Received with much shock and resistance from both his wife, Dorothy, and the congregation of Harvey Lane, Carey announced on a Sunday in January 1793 that in a few short months he would depart for Calcutta, in Bengal—the eastern most state of India. A church member, anonymous to humanity, but a hero in Heaven, changed the tide of discontent in a church meeting:

He reminded them how Carey had taught them to care about Christ’s kingdom… They had never been so drawn to intercession. “And now, God is bidding us make the sacrifice which shall prove our prayers’ [sincerity]. Let us rise to His call, and show ourselves worthy. Instead of hindering our pastor, let us not even be content to let him go; let us send him” (author’s emphasis) (p. 101).

Not only did the church and Dorothy’s spirits revive in enthusiasm for Carey’s undertaken, the Society and a cloud of financial benefactors rose up. But they were all novices to foreign missionary service—including Carey, as others later rehearsed:

Our undertaking to India really appeared at its beginning somewhat like a few men, who were deliberating about the importance of penetrating a deep mine which had never before been explored. Carey [volunteered], “I will go down, if you will hold the rope” (my emphasis). But before he descended he took an oath of [those] at the mouth of the pit that whilst [they] lived, [they] should never let go the rope (p. 108).

But red tape stood in the way, for the East India Company and its London officials, who managed its charter to do business in the Orient, did not grant access easily. At this time, well-known Englishmen came to Carey’s aid and counsel including William Wilberforce and John Newton.

During the delay in departure that the adversity brought, the embryonic beginnings of a team was formed which would prove to be critical to the success of Carey’s lifelong work in India. Thirty-two year old Carey met 24-year old William Ward, a printer to whom Carey “unfolded his desire and purpose of heart respecting biblical translations. Laying his hand on Ward’s shoulder as they parted, he said, ‘I hope, by God’s blessing, to have the Bible translated and ready for the press. You must come and print it for us.’ Neither ever forgot this” (p. 112).

Arriving in India in November 1794, Carey received the harsh reception from East India Company officials that he had anticipated. But God had prepared earnest Christian businessman George Udny. As John Newton had his Lord Dartmouth as benefactor, Udny seemed to fill this role for Carey. Managing Udny’s indigo factories, Carey, after six painstaking years, finally realized his objective of financial independence from the Society as it had long “been with a point of conscience that pioneer missionaries should be self-supporting as quickly as possible” (p. 160). In January 1800, Carey settled in what would become the home office of Baptist Indian missions in the city of Serampore, himself the clear leader of a “threefold cord [that] was never broken” but by death—William Ward (until 1823), Joshua Marshman (until 1837) and William Carey (until 1834). All of the financial resources they generated individually and corporately (and they were substantial over their lifetimes) were contributed to the Serampore ministry and shared “as every man had need” (Acts 4.35).

The trio was initially discouraged by the lack of fruit for their labors among the Indians steeped in their religions and stubbornly holding to the caste system that the missionaries found so antithetical to New Testament brotherhood. Contented they would be if but one Hindu or Moslem turned to Christianity. But S. Pearce Carey wrote of their intense desire for authentic believers, “Had they been satisfied with an indirect Christian influence, they would have escaped their disappointment. It was their agony for conversions which cost them their tears. They looked for nothing short of personal faith, a new birth, and wholehearted consecration. … Serampore was determined to boldly require every convert to abandon caste” (p. 193, 196). In 1806, they wrote to the Society in England, “The Cross is mightier than the caste” (p. 244).

As one reads S. Pearce Carey’s biography, he or she will be drawn to two great conclusions as to the eternal impact of Carey, Ward and Marshman. One, the Bible was no longer a lost book to the peoples of India. And, two, many Hindus and Moslems submitted to the truth of the Gospel and prepared themselves to win their own countrymen.

Especially true of Carey, his mastery of multiple languages not only opened the door to translate the Scriptures, but they made the formerly antagonistic British officials, loyal to the Church of England, beholding to the Serampore mission and to Carey specifically. When a new government college was founded in nearby Calcutta, Carey was invited to become one of its professors of linguistics.

When Carey enquired whether [the top government official] had been informed that he was a Nonconformist, he was assured that the provosts had faithfully reported all the facts. … And so it came to pass that Carey, who had been unable to secure from the East India Company any license to enter Bengal (the east most state of the country of India), and who had been forced to lie low for six years, and to camouflage his Christian purpose under a business pursuit … was not called to a position of high trust in the educational service of the British Government!

Furthermore, the work which established his linguistic fitness for this service (his just-printed Bengali New Testament, and his project to translate the whole Bible) had been pursued in fulfillment of the very function which the British authorities opposed (the conversion of Hindus to Christianity) (p. 207-209)

Carey’s professorship also gained him an advisory role to the government. “Nothing was published by the Government through 30 years in Bengali, Marathi, or Sanskrit without Carey’s endorsement!” (p. 215).

Great construction projects characterized the Serampore mission, but perhaps none greater than the printing works, supplied with fresh material by Carey and printed under the oversight of Ward. Not even a fire on March 11, 1812, that left “a shell of burnt and naked walls, with only a few business documents rescued” (p. 285) could douse the vigor for long with which hundreds were employed in printing and distributing the Scriptures translated into a plethora of languages. Ward wrote to England in December 1813, “Ten presses are going, and nearly 200 are employed about the printing office” (p. 305). The languages are listed on page 396:

The whole Bible – Bengali, Oriya, Hindi, Marathi, Sanskrit and Assamese

At a minimum, the New Testament – Punjabi, Pashto, Kashmiri, Telugu, Konkani “and 19 other languages”

Not one to accepted shallow Christianity in anyone professing conversion, including his own children, Carey eventually saw his entire family consecrated to the work of the Gospel. He wrote them often, S. Pearce Carey sharing many of his encouragements:

To Jabez who surrendered to go to Amboyna (modern day Indonesia): “When you meet with a few who truly fear God, form them into Gospel churches. [God] has conferred on you a great favor in committing you this ministry” (p. 304). And, “If true godliness prosper in your own soul, duty will be easy. If personal religion is low, your work will be a burden. Personal religion is the life-blood of all your usefulness and happiness” (p. 307). And more, “Let nothing short of a radical change of heart satisfy you in your converts” (p. 308).

To William who found himself serving in dangerous Mudnabati (interior Bengal) with his wife Mary: “There is much guilt in your fears, dear William. Mary and you will be a thousand times safer committing yourselves to God in the path of duty than neglecting duty to take care of yourselves” (p. 274).

Carey was greatly encouraged by his son Felix’s sacrifice to open Burma to the Gospel before Adoniram Judson arrived, but suffered greatly to bury his son after succumbing to “fevers” at the age of 37 (p. 358).

On a lighter note, Carey’s son Jonathan, acquired some of his father’s wit as evidenced by his poetic dialogue with “a young lady of his youthful admiration” (p. 282):

Madam,

After a long consideration Of the great reputation You have in the nation, I have an inclination To become your relation. To give demonstration Of this my estimation, I am making preparation To remove my habitation To a nearer situation, To pay you adoration. If this declaration Should meet your approbation, ‘Twill confer an obligation From generation to generation.

Jonathan Carey (A man of observation)

She replied:

Sir,

I received your oration, With much deliberation Of the seeming infatuation That seized your imagination, When you made your declaration, And expressed your admiration On so slender a foundation. But, after an examination And some little contemplation, I deem it done for recreation, Or with some ostentation, To display your education, By an odd renumeration Of words of like pronunciation Though of different signification; Which, without disputation, May deserve commendation. So I shall give much meditation To your quaint communication.

Of the duty of evangelism, Carey was focused on the long-term propagation of the Gospel in India. He wrote the Society in 1817, “In my judgment it is on native evangelists that the weight of the great work must ultimately rest” (p. 326). To this end they had labored so that in 1823, shortly after the death of Ward, in their distress they could “take comfort from the fact that nearly 700 Hindus had given up all their worldly connections and prospects for Christ since the year 1800, and that eight Indian students were currently being trained in their college for missionary service” (p. 361).

S. Pearce Carey ends his book with the following telling reflection of the fruit of William Carey’s life:

Carey knew that, though the living messenger was important to preach the Word, the Book itself, in the mother tongue of the people, was a permanent missionary, and also essential to the people of God “for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness,” that they might be entire, and wholly equipped for “all good works” (p. 396).

Comments

Post a Comment